Context & introduction

For the 7th edition of the HeroCTF, I decided to create some Android challenges for the first time of the history of the CTF. I wanted to do something that would force users to use Frida for dynamic analysis and prevent static analysis. Update : it didn’t work at all. The players threw the Android app code into LLMs, and the flag came out on its own.

But that’s okay, I will know it for next time.

So, I decided to write an article explaining the methodology I wanted players to use.

I will also take this opportunity to explain how native libraries work on Android and talk about native Java interfaces.

You might say that other articles already exist, but in this one I will use the example of a “real” application to illustrate my point.

Challenge Description

Try to find the password to open this vault!

I was told that it was dangerous to let my application install on a rooted machine. I fixed the problem! I was also told that it was safer to move sensitive functions from my code to a native library, so that’s what I did!

Don’t waste too much time statically analyzing the application; there are much faster ways.

The Java layer

In order to solve the challenge, the first step is to launch an Android virtual device (AVD) and install the application to see what it actually looks like. In the write-up I will use Android Studio AVD.

| |

Let’s install the APK on our device :

| |

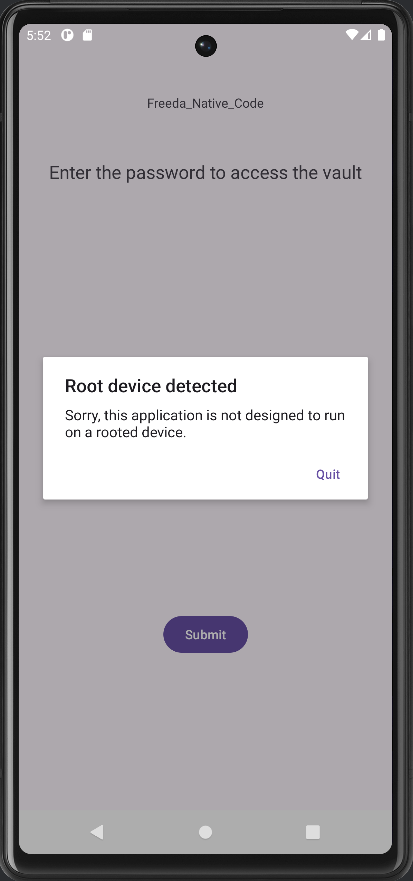

When launching the APK, we realize that the application detects that the AVD is rooted and it is not possible to enter passwords.

So I’m going to use JADX to decompile the APK and retrieve readable Java code.

| |

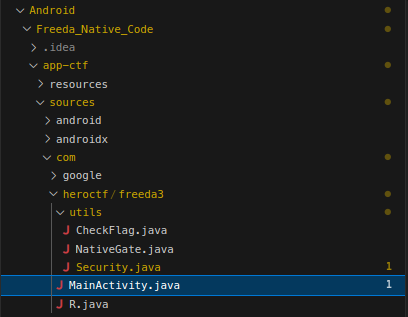

As we saw in the previous adb command, the package name is com.heroctf.freeda3, so the Java code for the main activity is located in the folder with the same path.

We can see that there is a NativeGate.java file. We can guess that a native library is being used.

| |

Crossing the bridge to JNI

The Java Native Interface allows developers to declare Java methods implemented in native code (often C/C++). This is not specific to Android but rather to Java more generally. Developpers use this for performance reasons (C/C++ are faster than Java) or to user already existing components.

The toolset for this is the NDK (Native Development Kit).

On the Java side, there are two ways to declare a native library:

| |

In the context of our application, we can see these lines of code indicating the use of a native library:

| |

To be able to use a function from the native library in your Java code, you must declare a native method. This way, when this method is called, the “paired” function from the native library is executed. So, the next line telles that the native library will export a function named nCheck(String str) :

| |

Continuing through static analysis, we found where the exported function is used :

| |

This line in CheckFlag.java suggests that this exported function checks the user’s input.

Reverse engineering JNI functions

We have just seen that the application uses a native library. The next step is to understand what the function does by reverse engineering the library.

What I didn’t talk about earlier is that here is two way to establish a link between a Java declaration and a C/C++ function.

The first way is by Dynamic Linking : the developer names the method and the function according to the specs such that the JNI system can dynamically do the linking. A native method name is concatenated from the following components:

- Java_ prefix ;

- Underscore separator ;

- Fully qualified class name.

In our case, if the nCheck() method is in the class com.heroctf.freeda3.utils.NativeGate, the C/C++ function must be named : Java_com_heroctf_freeda3_utils_NativeGate_nCheck.

If there is not a function in the native library with that name, that means that the application must be doing static linking. For reasons of obfuscation, for example, a developer may not want to use a recognizable name for their function, then they must use static linking with the RegisterNatives API in order to do the pairing between the Java-declared native method and the function in the native library.

RegisterNatives function is called at the very start of the library (in the JNI_OnLoad function).

| |

If we are facing static linking during our reverse engineering, we just have to look at the structure that is being passed to RegisterNatives to find functions.

But in our case, the app is using Dynamic Linking so we just have to open Ghidra and find the function called Java_com_heroctf_freeda3_utils_NativeGate_nCheck.

Cleaning Ghidra’s mess

Here is the function found in Ghidra :

| |

At the first glance, this is very messy and we can’t find Java arguments. But, we can add the jni_all.gdt file to help Ghidra recognize structures.

A really important things to know while reversing JAVA Native Librairies is that every function in native librairies takes JNIEnv* at first argument. JNIEnv is a pointer to a struct of function pointers to JNI Functions. The second argument will be the object that the function should be run on. For static native methods (they have the static keyword in the Java declaration) this will be NULL. Finally, the third argument is our argument, the String input.

The function can then be cleaned.

| |

That’s way better, we can see the JNI functions! It’s very simple to understand: a get_flag() function is called and its result is compared with the user’s input.

I will not loose any more time reversing the function and I will bring out Frida. Frida is a dynamic instrumentation toolkit. It allows you to inject JavaScript into the application process to hook functions and modify their behavior at runtime. It is particularly powerful here as it lets us interact directly with the native layer (C/C++) without needing to patch or re-sign the APK.

I’m going to use it to retrieve the value returned by the get_flag() function. But before that, I need to find its address.

Here is the list of commands :

| |

Line-by-line breakdown:

Process.getModuleByName(‘libv3.so’).findExportByName('get_flag') Finds the address of the get_flag export in the loaded libv3.so library (ASLR managed by Frida).

new NativeFunction(ptr(addr), ‘pointer’, []) Wraps the previous address as a C function with no arguments that returns a pointer.

getFlag() Calls the function, the result p is a NativePointer (char *).

p.readCString() Reads the null-terminated string at this address and returns it (UTF-8).

One small difference, however, is that the library is not loaded immediately into the application, so the most practical approach is to attach to script to an existing process. You must enter a random password into the GUI to force the load of the library.

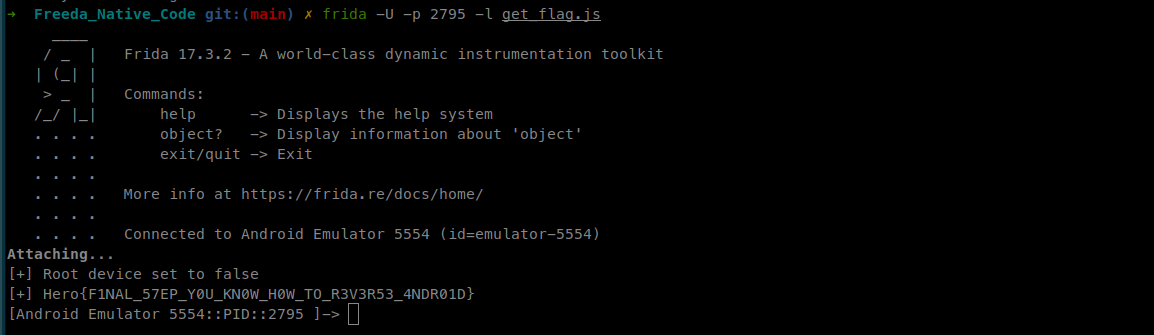

| |

Root detected - flag unavailable ; oh no, it looks like we missed something. Lets go back to Ghidra.

| |

Looking at the get_flag function, we see that a check_root() function is called, and if the result is equal to 0, then the code returns “Root detected - flag unavailable,” considering that the device is rooted. We must therefore rewrite the output value to make it appear that the device is not rooted.

| |

The script works like the one above: we hook the function that checks the flag by finding its address, then we rewrite its return value. The value will always be 1, as if the device were not rooted

Now we can combine the two parts:

| |

And here is the flag !

Flag

Hero{F1NAL_57EP_Y0U_KN0W_H0W_TO_R3V3R53_4NDR01D}

References

- https://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/technotes/guides/jni/spec/functions.html

- https://valsamaras.medium.com/tracing-jni-functions-75b04bee7c58

- https://developer.android.com/ndk

- https://www.ragingrock.com/AndroidAppRE/reversing_native_libs.html

- https://developer.android.com/ndk/guides/jni-tips

- https://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/technotes/guides/jni/spec/functions.html